by EE Ottoman

The snow started in the evening, big, heavy flakes falling into the dark. Erin took a book and cup of tea to bed and hoped it would stop sometime during the night.

In the morning, though, the world was white, soft and silent, snow still falling from a dark gray sky.

Erin stood at the living room window, coffee in hand, and watched the snow fall. About five inches covered her car, with even more blown into sweeping dunes around it. The driveway snaked from her old farmhouse up to the road, both heavy with untouched snow.

Beyond the small stand of trees that divided their properties, Erin could just make out her neighbors, bundled up and trying to dig out their cars. The schools weren’t closed, then, probably just on delay.

She’d have to dig out, too, eventually. They weren’t close enough to town for the plows to come clear the roads anytime soon. Though Erin had nowhere to be. She could afford to wait, at least until it stopped snowing.

Today would be a jeans, heavy sweater, and wool socks kind of day. Erin changed into one of her oldest sweaters, heather green and going to pieces at the bottom and cuffs; jeans stained with dark patches of book glue; and fuzzy socks. She braided her hair to keep it out of her face.

After pouring her second cup of coffee, she went to look at what projects she had to work on in the office. She’d always had a book to work on in her own time, even back when she was director of the university library’s preservation unit and got to repair books every day. There was a difference between doing something because it was her job and doing something because she loved it. These projects were hers and only hers, not dictated by a library budget or the fact that more-used items needed to be worked on first.

One of the things she’d looked forward to the most after retiring was these little projects.

A stack of about six hardcover books she’d bought at the local used bookstore awaited her attention. Erin put aside her coffee cup and picked up a volume about the birds of New York and how to identify them. The publication date was 1966, the book clothbound in unassuming brown, now faded, with gold lettering. The lettering was what had originally caught Erin’s eye. It was in fairly good shape, although the spine was detached, causing the boards to break away from the text block as well. Some of the other books needed full rebinding, which would take more time, so Erin set them aside to work on later.

She used a utility knife to slice through the binding cloth, fully detaching the spine and boards from the text block. She set the spine and boards aside and put the text block, now bare, spine up, in a wooden clamp.

The sound of wheels crunching through snow made her glance at the window. It sounded too close to be her neighbors or some brave soul on the road. Setting aside her tools, she went to look outside.

A pickup truck with a snowplow attached crawled slowly up the driveway, clearing as it went. Erin pulled open the kitchen door and leaned out into the cold.

The truck had parked at the top of her driveway, and the door swung open. Rye climbed out, big, square body bundled up in work boots, coveralls, farmer’s jacket, and wool cap.

“Hey,” they called, and waved at Erin.

“Hi.” She waved back as Rye waded through the snow and up the steps to the house.

“I thought I’d come plow you out.” Rye kicked the snow off their boots before stepping into the kitchen. “Since I finished clearing off my driveway.”

“Thank you. I don’t want to put you through the extra trouble.” Erin closed the door behind Rye and turned to see them pulling off their wool cap and dusting moisture from their dark hair.

“It’s no trouble.” Rye looked at the floor, cheeks pink. Erin couldn’t tell if it was from the cold or from bashfulness.

“Well, thank you then.”

Rye just nodded. “Let me finish it up.” They put back on their cap and turned toward the door.

“When you’re done, come back in, please. Have some tea, something to eat.” It was the least Erin could do in return for not having to shovel the driveway. Not to mention the thrill that went through her at the idea of sitting down with Rye.

When she’d moved here a few months ago, she’d heard of them as one of the few other trans people in the area. They had friends in common: Emma, who ran the local library, and Peter, who ran the historical society. Peter liked throwing dinner parties, and Emma liked introducing people, so it was inevitable that Erin and Rye would meet and be friendly. They were still hovering in that awkward space between friends and acquaintances, although Erin very much hoped the two of them would come down to settle on the side of friendship.

Rye was quiet, she knew. They owned a small farm and sold at the local farmers market. The two of them had spoken about what was good and what was seasonal, so Erin knew they had eating in common.

Rye wasn’t looking at her. They’d gone all quiet, and she thought they were going to say no until they looked up at her and nodded. “That would be nice.”

“Great.” She beamed.

They just nodded again and pulled open the door, letting in a small burst of snow.

She filled the electric kettle and turned it on, wishing she’d asked Rye if they preferred black tea or herbal. She put both on the counter, just to make sure. There was cake Erin had made yesterday, dark with molasses, flavored with cloves and cardamom. There was also homemade cheese, herb and olive bread from the day before, and goat cheese Erin had bought from a tiny goat farm a forty-minute drive from her house. She put the cake and bread in the oven to warm.

Outside, Rye’s truck moved up and down the driveway until all of the snow had been cleared except for a small patch around Erin’s car. Rye parked and climbed out, taking a shovel from the truck bed.

Erin pulled on her boots and coat, stuffing her hands into mittens as she stepped out into the snow. “Let me help.”

She picked up her own shovel and trekked across the snow to where Rye stood.

“You don’t have to. I told you I don’t mind.”

Rye didn’t stop her, though, from digging into the snow around her car. “With two of us, it will go faster.” That, and Erin felt bad making Rye both plow the driveway and dig her car out, too. She shoveled a space big enough for her to get to the back of the car and popped the trunk. There was an old broom in there she used to sweep the snow off the car itself.

“Fair enough.” Rye bent to shovel again, leaving Erin to sweep.

By the time she’d finished uncovering the car, they’d managed to make enough space for her to easily get it out and down the driveway.

“Now we eat.” Erin stowed the broom back in the trunk while Rye put their shovel away.

They both climbed over the snow back into Erin’s kitchen. Inside, they shed coats, hats, scarves, and mittens, hanging everything on pegs and leaving their boots on the rubber mat beneath.

The food was warmed all the way through, Erin was happy to find, although the water had to be reheated. “Black tea, herbal?” She gestured to the row of tea boxes while she turned the kettle back on.

“Black is fine, or whatever you’re drinking.” Rye shuffled a little, looking ill at ease standing sock clad in Erin’s kitchen.

“There’s cake, bread, and cheese.”

Rye brightened. “I would love some cake.”

Erin cut them a slice, and by the time she’d finished, the water was boiling again. She made them both tea while Rye ate their cake.

“It’s really good.” Rye smiled at her when Erin turned to see he’d eaten almost his entire piece.

“Thanks.” She put more slices of cake on plates, along with bread and cheese, and set them on the kitchen table.

They sat on either side of the table, each with their mug of tea, the food between them.

“So how’s your farm and the animals?” Erin reached for her own slice of dark, moist cake.

“It’s been going all right.” Rye shrugged, hand circled loosely around their mug. “Been busy getting everything ready for winter.”

“Do you put up a lot of food and things?”

Rye smiled. “Yeah, I do put some away for winter—root vegetables, honey, soap, candles, jarred preserves. I’ll sell a lot of it, of course.”

“Of course.” Rye’s farm was their livelihood, after all, and times were tough for farmers. Still, she hoped they were able to keep at least a little of it for themselves.

“What about you?” Rye reached for a slice of bread. “Surviving Upstate New York winter all okay?”

Erin laughed. “I lived here years, and I haven’t been away that long, but yes, it’s been all right. Especially with as mild as the beginning was.”

Rye nodded. “It’s always strange when we don’t have snow in November or December even.”

Silence fell between them.

“If you don’t mind me asking . . .” Rye put their mug aside again. “Why did you come back here? This doesn’t seem like the place most people retire to.”

Erin looked down at the mug of dark tea in her hands. She didn’t say she’d come back here because this was where she’d lived when she’d been married, when she’d had a family, children who still spoke to her—in this beautiful part of the country where for a long time she’d assumed she’d live for the rest of her life. Before she’d come out and transitioned, before everything had been taken away. She lifted the mug and took a sip. “It’s quiet here.”

“It is.” Rye’s voice was gentle and calm. They didn’t ask further, just let what she’d said be. The easy way they held themselves made Erin want to keep talking, want to tell them about it all.

They were both silent for a moment, and then Erin sat forward, elbows on the scarred wood of the table. “Can I ask you a personal question?”

“Depends on what it is.” Rye looked wary.

“Why use the singular ‘they’?”

That shook a startled laugh from Rye. “Why not?” They picked up their mug and leaned back in their chair. “I go by male pronouns, too—tends to make people feel more comfortable—but the older I get, the less gender means, you know?”

In some ways, Erin didn’t know, couldn’t imagine knowing, but in others . . . she thought about before she’d transitioned, what that had been like, what it was now. “I guess.”

Rye tilted their head to the side. “You know, when I was younger, it was all about being a real man.” They smiled like they were making a joke. “But at the end of the day, I’m more me than anything, and I’m all right with that.”

Erin thought about the truth in what they’d said. “I guess to me, my womanness is part of me. There isn’t a way of separating the two.”

She half expected Rye to protest, but instead they nodded. “I understand that.”

They just let that be between them for a beat or so, and then Erin reached for her mug, and Rye shifted where they sat. Too much intimacy too soon. They both looked away.

Erin cleared her throat. “So what do you do when you’re not working?”

Rye hesitated. “I hike, camp, and I like to forage for mushrooms, wild leeks and things that grow naturally here.”

“Sounds interesting.” It sounded dauntingly outdoorsy to Erin, who couldn’t remember the last time she’d gone camping.

“What do you do?”

“I repair books.” Erin thought about leaving it at that, but then stood. “Let me show you.”

She led the way into the office and undid the clamp holding the book she was working on, handing it to Rye.

“I find books like these at used bookstores and library sales, take them home, and restore them.” She watched Rye turn the half-disassembled book over in their hands.

“You know, when I was working, we mostly just made sure books were functional, that they would last however many more years and be readable, at least. But for my own projects, I want more to make books beautiful, you know? Like, take a book that was mass-produced to be a consumer object and turn it into a piece of art. Or take a book that was originally made to be beautiful but has maybe not aged well and make it beautiful again in a different way.”

“After you’re done making these books beautiful, where do they go?” Rye turned the book over a second time, then opened it carefully to look inside.

“I give them away.”

“That’s a beautiful gift to receive.”

Erin could feel her cheeks heating. “Thank you.” Then an idea occurred. “Do you like birds?”

It seemed like a ridiculous thing to say, but Rye smiled. “I do. I’ve been known to participate in some of Cornell’s bird identification research, actually. Just data collecting, you know.”

Erin stuck her hands in the pockets of her jeans. “If you want, when I’m done, you can have this one.”

Rye went still. When they looked up at her, their eyes were wide with real surprise. “Are you sure?”

Rye held the book almost reverently now, and Erin looked at the floor to keep from staring at their large hands against the binding cloth of the cover. “Yes. I mean, I would be doing the work anyway.”

“Well, thank you.” Rye held out the book to Erin, who took it and put it back on the worktable.

They returned to the kitchen. “I should get going,” Rye said. “Do you need help cleaning up?” They nodded at the table with food, plates, and mugs still on it.

“I’ve got it.” Erin waved them off, although she did let Rye help her carry the dishes to the sink.

“Are you sure I can’t dry at least?”

Erin gave in. “Sure.” She turned on the water and handed Rye a dish towel.

She washed and they dried until the dishes were put away.

Rye hung up the dish towel and wiped their hands dry on their pants. “Thank you so much for the food.”

“Thank you for plowing me out.”

Rye nodded, smiled, and went to pull on their boots.

She watched them dress for the cold. Outside, the wind was still blowing clouds of snow into the air. The sky was the color of pale slate, and the trees looked even darker than that against the sky, heavy with snow.

All bundled up again, Rye nodded one last time and pulled open the kitchen door.

“Be safe,” Erin called after them. Rye turned and raised their hand in a wave.

She watched them make their way to their truck. The truck’s engine rattled and coughed but started up. Rye let it warm for a minute or two.

Erin went back inside. She stood at the window watching until the truck pulled down the drive and into the road beyond.

Then she turned away and went back to her books.

***

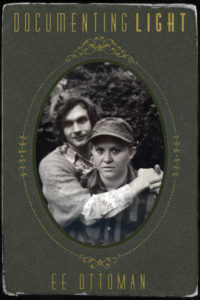

If you enjoyed this story, you may also enjoy EE Ottoman’s novel Documenting Light

If you look for yourself in the past and see nothing, how do you know who you are? How do you know that you are supposed to be here?

When Wyatt brings an unidentified photograph to the local historical society, he hopes staff historian Grayson will tell him more about the people in the picture. The subjects in the mysterious photograph sit side by side, their hands close but not touching. One is dark, the other fair. Both wear men’s suits.

Were they friends? Lovers? Business partners? Curiosity drives Grayson and Wyatt to dig deep for information, and the more they learn, the more they begin to wonder — about the photograph, and about themselves.

Grayson has lost his way. He misses the family and friends who anchored him before his transition and the confidence that drove him as a high-achieving graduate student. Wyatt lives in a similar limbo, caring for an ill mother, worrying about money, unsure how and when he might be able to express his nonbinary gender publicly. The growing attraction between Wyatt and Grayson is terrifying — and incredibly exciting.

As Grayson and Wyatt discover the power of love to provide them with safety and comfort in the present, they find new ways to write the unwritten history of their own lives and the lives of people like them. With sympathy and cutting insight, Ottoman offers a tour de force exploration of contemporary trans identity.

Available late summer 2016 from Brain Mill Press

More information at documentinglight.com

***

An excerpt from Documenting Light

Chapter 1

The first thing Wyatt thought when he saw the apartment was that it was beautiful. The ceilings were high, with some orient patterning across each. The doorways in the living room were tall, sweeping arches, and every room had huge windows. There was a built-in bookcase and a fireplace in the living room, with a fireplace in the bedroom as well. The whole place was fresh-painted white walls and gleaming hardwood floors.

“Forget about Mom.” Jess turned in a slow circle in the living room. “I want to live here.”

“Yeah, if either of us could afford it.” Wyatt stuck his hands into his pockets and looked out the living room window at the tree-lined street.

Their mother was a different story. “It’s not the farm.” She ran her hands over the mantle of the fireplace in the living room, sidestepping the couch the moving men had left jutting into her path. Her big silver hoop bracelets slid and clicked against the wood. “How am I going to walk the dogs without plenty of outside space?”

“You’re not bringing the dogs.” Wyatt took her hands, turning her gently toward him. “Remember? We talked about this. The Baker boys love them, they’ll take good care of them.”

“And the farm?” She looked confused, but then they’d expected this. They’d been told the move would be hard and disorienting for her.

“Yeah, they’re running the farm now, and you’re going to live here, where you can be close to Jess and me.”

Timothy, Jess’s fiancé, staggered past, his small frame laden with boxes for the kitchen.

“And Timothy,” Wyatt added with a pang of guilt. He was glad Timothy was here, even if he would’ve preferred this to be family only. “It’s going to be good.”

She still didn’t look convinced, though.

“Come on.” Wyatt guided her over to one of the built-in bookcases, where boxes of books were already stacked. “Let’s get these books unpacked. You know how you want them organized.”

He opened one, and for a moment she stared into the box like she’d never seen its contents before. Then her face brightened. “Oh, yes. These are my books on herbal remedies”—she pulled out a handful—“and herb gardening. I see some about wild herb identification in here, too. They’ll each need to go together in their own sections.”

“Good.” Wyatt sat back on his heels as she sorted the books, placing each on the shelf. The doctor had told him that breaking the move into pieces that were manageable for her was the key.

“The rest of these books are on gardening?” She tapped the lid of the next unopened box.

“I’m assuming some of them are.” Wyatt ripped the tape off the box and opened it. “But your books on tree husbandry are probably here, too. So each their own section?”

“Oh, I have far too many books on those topics for them to be each their own section. They’ll have to be broken down further.”

“Then you’ll have to do it, and I’ll put books where you tell me to, but I don’t know this stuff well enough to sort them.”

“If you’d paid attention when you were growing up, you would know.” But she was smiling, that little teasing smile that said even though she had her mom voice on, she didn’t mean it.

It made Wyatt smile back, even as his stomach twisted because he hadn’t seen that smile in months and had begun to think he’d never see it again.

It was one of those things you had to let go of. Or at least that’s what he’d been telling himself.

“You two look like you’re doing good in here.”

He turned to see Jess in the doorway looking disheveled in her oldest clothes, curls escaping from the ponytail at the nape of her neck.

“Unpacking?” She smiled encouragingly.

“Yeah.” Wyatt waved his arm, taking in the open boxes and bookcase. “We’re doing good, organizing the books.”

She stuck her hands in her jeans pockets and walked over to look at what they had on the shelf so far. “Well, I think the moving people have gotten everything in.”

“I’ve been organizing by topic. Here, hold this.” He thrust a stack of books at Jess.

“You know what, Wyatt?” Jess obediently took the books. “I’ll help Mom here for a while if you want to move the boxes in the hall up into the attic. The landlord told us we could use the space up there for storage.”

“Sure.” Wyatt dusted off the legs of his jeans as he stood and headed into the hall.

Timothy was in the kitchen unpacking boxes of cookware. “You want to order Chinese sometime soon?” Wyatt leaned into the kitchen, hand braced against the door frame.

“Sure. Chinese sounds good.”

“I have to move some boxes into the attic, but when I get back I’ll order.”

Timothy nodded. “Tell me how much and I’ll pitch in.”

For a moment, Wyatt wanted to say, You don’t have to, she’s not your mother. But that would come out far harsher than he meant it. “Sure. I’ll let you know.” He ducked back into the hall.

His mother’s apartment was on the second floor. It took him a few minutes to find the door that led to the attic. Once he did, it wasn’t as bad as he thought it might be. The stairs and attic space were well-lit at least, not just by the ceiling lights but also from a circular window set into the front of the house that let the last of the day’s sunlight and warmth spill in. It was dusty up there, but not dirty per se, and the floor felt sturdy under him, which made it about a hundred percent safer than the attic of the old farmhouse where he’d grown up.

Wyatt shifted the boxes one at a time up the stairs. It was hard to tell where to put them because everything in the attic seemed to be randomly arranged, without any clear way of identifying what belonged to whom. He opted to push his mother’s boxes back as far as they would go against the wall opposite the stairs—although he ended up having to stack them near the window simply because that was the only space left.

The closer he got to the window, the hotter it got, causing pricking points of sweat to break out along his arms and the back of his neck. His eyes began to water against the light and dust, and when he’d moved the last box up Wyatt sat cross-legged on the floor.

He should go back down and order Chinese or see how book sorting was going. Instead, he tipped his face back and closed his eyes, taking several deep breaths.

They’d been at the old house packing until one or two o’clock in the morning. Then Timothy had arrived with the truck at five. Wyatt’s limbs were heavy, the muscles in his back ached with every move, and they still had the entire apartment to unpack. He rotated his shoulders, trying to get the kinks out.

From the stairs, Jess’s laugh, loud and strong, drifted up, his mother’s laughter, too, thank God.

It was . . . strange, though, hearing them down there with him alone up here.

He stood up, trying to brush dust off his ass as he did, and didn’t realize he’d misjudged until pain exploded bright and hot behind his eyes. Wood, dust, and dirt showered down on top of him. “Shit!” He doubled over, hands going to the back of his head, which he’d rammed straight into a beam. “Fuck!”

The first shock gave way to waves of pain encompassing his entire head, bad enough to make his eyes fill with tears. He went back down onto his knees and for a moment thought maybe he should start screaming for Jess, who was a nurse after all. The pain was already lessening, though, so Wyatt just rocked back and forth while groaning pitifully.

Eventually, it diminished to the point that he could take his hands away, inspect them carefully for blood, and stand back up.

Some of the pink insulation had gotten loose right above where his head hit the beam, but otherwise nothing looked any worse for the wear. You weren’t supposed to touch insulation, if he remembered correctly, but on the other hand he didn’t want to leave pieces hanging out. He pulled the sleeve of his flannel shirt over his hand and tried to stuff the insulation back into the ceiling. Of course it didn’t go back in easily. Wyatt put his full weight behind it and shoved up arm first as hard as he could. The entire thing crunched, and then a large piece fell out, landing at his feet.

“Well, fuck.” Wyatt looked accusingly at the hole he’d made.

There was something behind the insulation. He reached up, fingertips brushing paper. He pushed his hand farther in until he could feel an edge and then pulled. The whole thing came away at once.

It was an envelope, one of the large ones people used to send papers in, brittle and already falling to pieces as he held it. It felt too light to contain papers. Wyatt opened it as carefully as he could.

There didn’t seem to be anything in there when he inched his fingers in, so he turned it upside down to be sure. He squeezed the bottom and shook the envelope several times. Something fell out and fluttered to the floor.

Wyatt bent to pick it up.

It was a photograph. Not a particularly large one, a little bit faded, the corners slightly tattered.

Two men sat, one darker skinned and one fairer, each on opposite sides of a table but facing the camera rather than each other. They wore matching dark suits and posed almost identically, with one hand resting on the tabletop. The light-skinned man’s legs were crossed, his pose more relaxed. His companion stared straight at the camera. He seemed almost nervous in his tense focus, in the way he held himself. Neither of them smiled, but there was something almost candid about the shot, as if the men were waiting for the actual portrait to be taken. As if the moment after this one, the fairer man had uncrossed his legs, sat up straighter, while his companion had loosened his pose, letting some of that energy go, sitting with more confidence. In this moment, though, the two were caught in anticipation.

The back of Wyatt’s neck pricked, and he turned the photograph over, but there was nothing to see there. He picked the envelope up again and inspected it. It was truly empty this time and also completely unmarked.

What kind of photograph got stuck in an envelope and shoved up into the ceiling of someone’s attic?

He looked at it again, the two of them sitting there, caught in that moment, both of them unguarded, their hands slid a little too close together on the table.

Maybe the better question was, What kind of photograph do you hide?

Wyatt stared for another second and then shook his head. It was probably nothing, just an old picture that had been forgotten about.

There was something about the two of them, though. His finger went to trace the shape of the fairer one, the angle of his jaw, the way the light outlined his face—it felt family in a way that resonated deep inside Wyatt’s body.

“Who were you?” He kept his voice low. “Were you hiding?”

There were, of course, the obvious theories, reasons a picture like this might be put away. He could imagine that they had been a couple. This one incriminating piece of evidence tucked away to keep it from being destroyed after the deaths of the people it portrayed.

Wyatt had never hidden being queer, but when it came to everything else, all he did was hide. The weight of passing through the world as something he was not was almost crushing sometimes. For people to look at him and see a man when he so clearly wasn’t felt like the worst kind of lie. It was like having an empty place inside of you, a rough, torn-out spot to be guarded, hidden, lied about. A bruise you could forget even hurt until it was touched.

Had they known?

He tucked the photograph into his breast pocket and descended the stairs to his mother’s new apartment.

***

About the Author

EE Ottoman grew up surrounded by the farmlands and forests of Upstate New York. They started writing as soon as they learned how and have yet to stop. Ottoman attended Earlham College and graduated with a degree in history before going on to receive a graduate degree in history as well. These days they divide their time between history, writing, and book preservation.

EE Ottoman grew up surrounded by the farmlands and forests of Upstate New York. They started writing as soon as they learned how and have yet to stop. Ottoman attended Earlham College and graduated with a degree in history before going on to receive a graduate degree in history as well. These days they divide their time between history, writing, and book preservation.

Ottoman is also a disabled, queer, trans dude whose correct pronouns are: they/them/their or he/him/his. Mostly, though, they are a person who is passionate about history, stories, and the spaces between the two.

EE Ottoman grew up surrounded by the farmlands and forests of Upstate New York. They started writing as soon as they learned how and have yet to stop. Ottoman attended Earlham College and graduated with a degree in history before going on to receive a graduate degree in history as well. These days they divide their time between history, writing, and book preservation.

EE Ottoman grew up surrounded by the farmlands and forests of Upstate New York. They started writing as soon as they learned how and have yet to stop. Ottoman attended Earlham College and graduated with a degree in history before going on to receive a graduate degree in history as well. These days they divide their time between history, writing, and book preservation.